Boiling Point: Climate Council’s ‘Hot’ Tricks Exposed

Shrunken screens, cherry-picked data, and a climate council desperate for headlines… the real heat is in the spin!

Shrunken screens, cherry-picked data, and a climate council desperate for headlines… the real heat is in the spin!

The Climate Council are once again up to its old tricks, misleading the public with breathless headlines proclaiming “All-Time Heat Records Smashed – This Is Climate Change.”

It sounds alarming. It sounds authoritative. But it is profoundly misleading.

What the Climate Council conveniently omits is that many of these so-called “records” owe less to the climate and more to a quiet but consequential change in how temperatures are measured, specifically, a sneaky change implemented by the Bureau of Meteorology (BOM): the shrinking of Stevenson screens.

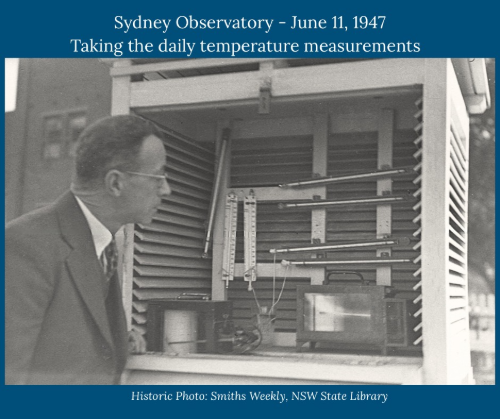

Stevenson screens are white, louvred enclosures designed to house thermometers while shielding them from direct sunlight, thereby preventing artificially inflated temperature readings. For most of Australia’s meteorological history, the BOM used a large Stevenson screen with an internal volume of roughly 0.23 m³.

Over the past two decades, however, the BOM has progressively replaced these with small Stevenson screens with an internal volume of just 0.06 m³, less than one-third the size.

Before COVID conveniently diverted public attention, I questioned the BOM about this change during a Parliamentary hearing. I asked a simple question: why was the specification of the measuring equipment altered? Why were the screens shrunk?

The BOM could not provide an answer.

Common sense alone should raise alarm bells. A smaller enclosure traps heat more readily, particularly on hot, still summer days, precisely the conditions under which “record-breaking” temperatures are most likely to be proclaimed.

But this is not merely common sense. It is settled science.

In 2015, a peer-reviewed study published in the International Journal of Climatology, titled “Impact of Two Different-Sized Stevenson Screens on Air Temperature Measurements,” examined precisely this issue.

The findings were unequivocal. Smaller Stevenson screens “tended to overheat daily maximum air temperatures (0.54 °C on yearly average),” and, crucially, during mid-summer could record temperatures as much as 1.7 °C hotter than larger screens - a great way to create new "records".

In a world where every tenth of a degree is treated as a planetary emergency, this is not a rounding error; it is the difference between a headline and a non-event.

Yet the BOM refuses to acknowledge the implications of this peer-reviewed research and continues to insist that the downsized screens make no statistically meaningful difference. The Climate Council, for its part, parrots the resulting data without a hint of curiosity or scepticism.

The result? Manufactured records and manufactured panic.

And this is only part of the deception.

The Climate Council also neglects to mention that most of the weather stations now trumpeting “all-time heat records” have been operating for barely two decades. None extend back to the 1930s, let alone earlier periods when Australia endured some of its most extreme and well-documented heatwaves.

Stations with genuinely long-term records paint a very different picture, one that does not support claims of unprecedented heat.

Sydney provides a particularly inconvenient example for the alarmists.

Once again, this summer failed to match the heat endured by the convicts of the First Fleet during the summer of 1790-91.

On 27 December 1790, measured just a stone’s throw from modern-day Observatory Hill, Sydney's temperature reached 108.5 °F (42.5 °C) by 1:00 pm, before peaking at 109 °F (42.8 °C) at 2:20 pm.

That was 236 years ago.

These observations were recorded by Watkin Tench, a British marine officer and First Fleet chronicler, in his 1793 book A Complete Account of the Settlement at Port Jackson.

Tench was no casual diarist. He was a disciplined observer, trained in the scientific methods of his time, using a high-quality thermometer manufactured by Ramsden, the foremost scientific instrument maker in England.

Describing the heat of 27 December 1790, Tench wrote that “it felt like the blast of a heated oven.”

And this was not an isolated spike.

The following day again exceeded 100 °F, reaching 40.3 °C (104.5 °F). In February 1791, Sydney recorded temperatures of 42.2 °C (108 °F), with even higher extremes reported inland at Rose Hill (modern Parramatta).

Tench wrote:

“But even this heat… was judged to be far exceeded in the latter end of the following February… At Rose Hill it was allowed, by every person, to surpass all that they had before felt, either there, or in any other part of the world.”

Anticipating modern attempts to dismiss his observations, Tench went out of his way to document his methodology, noting that his thermometer was hung in shaded, open air, never exposed to direct sunlight, and positioned several feet above the ground, detailing in his journal:

“This remark I feel necessary, as there were methods used by some persons in the colony, both for estimating the degree of heat, and for ascertaining the cause of its production, which I deem equally unfair and unphilosophical. The thermometer, whence my observations were constantly made, was hung in the open air, in a southern aspect, never reached by the rays of the sun, at the distance of several feet above the ground.”

In other words, no urban heat island, no air conditioners, no concrete canyon, no traffic and solar panels strategically placed to reflect heat on the Stevenson Screen (as the BOM where caught red-handed doing a few years ago), just bushland and honest measurement.

In 1790, Sydney’s population was around 1,700. Today, it is over five million. Observatory Hill is now surrounded by steel, glass, asphalt, tens of thousands of air conditioners venting waste heat, and roughly 160,000 vehicles crossing the Harbour Bridge daily within 100 metres.

If anything should be inflating modern temperatures, it is this.

Contemporaneous accounts corroborate Tench’s measurements. Lieutenant-Governor David Collins described mass wildlife deaths as streams dried up, bats dropped dead from trees, and birds littered the ground, gasping for water.

“Fresh water was indeed everywhere very scarce, most of the streams or runs about the cove being dried up. At Rose Hill [Parramatta], the heat on the tenth and eleventh of the month, on which days at Sydney the thermometer stood in the shade at 105°F [40.6°C], was so excessive (being much increased by the fires in the adjoining woods), that immense numbers of the large fox bat were seen hanging at the boughs of trees, and dropping into the water… during the excessive heat many dropped dead while on the wing… In several parts of the harbour the ground was covered with different sorts of small birds, some dead, and others gasping for water.”

Governor Arthur Phillip himself noted that more than 20,000 bats were seen dead within a single mile at Rose Hill, their bodies contaminating local water supplies.

“... from the numbers [of dead bats] that fell into the brook at Rose Hill [Parramatta], the water was tainted for several days, and it was supposed that more than twenty thousand of them were seen within the space of one mile.”

This was not metaphorical heat. It was lethal.

And yet today, mass bird and bat deaths are more commonly linked to industrial steel wind turbines than to heatwaves, an irony rarely acknowledged by climate campaigners.

Tench, for his part, concluded that Sydney’s climate was “changeable beyond any other I ever heard of”, which was a sober observation based on lived experience, not computer models or media talking points.

Fortunately for the early settlers, Governor Phillip and his successors did not believe the climate could be stabilised by culling cattle, restricting transport, or reorganising society.

Two centuries later, one wonders whether we have become more scientifically enlightened or merely more easily frightened.

“There is no way that we can predict the weather six months ahead beyond giving the seasonal average.”

– Stephen Hawking

Join 50K+ readers of the no spin Weekly Dose of Common Sense email. It's FREE and published every Wednesday since 2009